The land in Igbo cosmology is unqualifiedly sacred and in the pre and early colonial Igbo societies elaborate rites must be performed for cleansing whenever it is violated by certain egregious human misconducts like murder. Otherwise, the particular community in which the violation took place would discover that it has murdered sleep. Similarly, the Igbos believe, the souls of the unburied dead, and even those denied decent burial, hardly rest and are wont to haunt their living kith and kin until proper rites of transition are done. More universally, societies which fail to confront, come to terms with and remediate as much as practicable the more unpalatable of their past frequently have the unresolved contradictions and offence of that past haunt them like the Coleridgian albatross.

These axioms and beliefs, and much more, find convergence in the story and essence of the Asaba Massacre; a candidate for the dubious prize for the ugliest chapter of Nigeria’s history featuring the industrial scale murder of Nigerian citizens by agents of the Nigerian state. We as a nation, at any rate the officialdom, have been at best disinterested in interrogating the infamous event. The only attempt, tangential at that, was the Justice Oputa led Human Rights Violations Investigation Commission (“Oputa Panel”) hearing of the petition of Ohaneze Ndigbo on human rights abuses suffered by Igbo people during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967-1970. The inconclusive end of the Oputa Panel is as trite as it is sad.

Nonetheless, the national pretend amnesia on the Asaba Massacre is akin to hiding under one finger. It is not going to go away unless and until we confront the ogre that its memory represents. Beyond the men, mostly, and a few women and children too, massacred on that dark day, their relatives and the Asaba and surrounding communities have had to contend with an insufferable burden; living for decades with the denial by their country of a historic atrocity of genocidal proportions visited on them by their own country’s army. Even worse, the monumental injustice has festered and, albeit partially, like a metastasizing malignancy spurned ever since the countrywide banality of bloodletting which has been on a crescendo over these past five years.

It is axiomatic that Nigeria’s conscience remains seared by the Asaba Massacre. And conscience, as Uthman dan Fodio admonished us, is an open wound which can only be healed by truth. It is only on the foundation of truth that a genuine reconciliation can be built. But the question is, as the colonel in Aaron Sorkin’s ‘A Few Good Men’ shot back at counsel in the film’s feisty cross examination, can Nigeria handle the truth? Is it ready for the truth? The answer is that Nigeria had better be ready because without the reconciliation which is a function of the truth its progress would remain suspended.

This is where the project of memorializing the Asaba Massacre assumes the category of article of faith for all true patriots; the first giant step towards embracing a historic truth, as unpalatable as it may be, which would enable a long overdue catharsis. But make no mistake about it, this is a monumental and daunting task especially considering the official policy of denial we had earlier adverted to. The cause for optimism, however, lies in the fact that the project mastermind, Chuck Nduka-Eze, comes into the task as well armed as only very few could possibly be.

He has the right pedigree, being the scion of one of the most resilient Nigerian anti-colonial fighters. He also has the mental conditioning and stamina, with over thirty years of intense multi-jurisdictional practice of different areas of law including a decade as barrister with the Crown Prosecution Service in the United Kingdom. He was also counsel for the Asaba Community at the Oputa Panel. And finally, he can lay some legitimate claim to ownership of the tragic story; being not only a highly regarded High Chief and community leader in Asaba but also having to suffer the trauma of his mother as one of the casualties. As Chinua Achebe was wont to remind his audience, it is a prerequisite to our wellbeing to always know where the rain started to beat us. The Asaba Massacre Memorial Project would help us in that regard. It is in conception and ambition a lodestar in Nigeria’s journey to a much needed national reconciliation, justice and brotherhood across its well known debilitating fault lines.

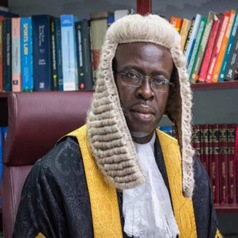

CHIJIOKE OKOLI, SAN

0 Comments